Cost and feasibility of future energy solutions

By Sam Stephens and Andy Boston

I recently met with some ‘Innovation Consultants’ who had been working with National Grid, one of ERP’s members. As admitted non-engineers, what struck them was how little they understood about the UK power system prior to working with National Grid, and also how complicated it is. What also struck them was their ignorance of simple engineering principles that govern the system, particularly the fundamental concepts of voltage and current.

While this is somewhat of an aside, it raises some important points; our power system is complicated but it is based on fundamental engineering principles, which the majority of the general public do not understand. Fortunately, we’ve managed to make the concept of energy as simple as running water – plug in an appliance, fill up a car, switch on the boiler. Unfortunately, the cost of energy is still highly distorted by subsidies, natural monopolies and an under-pricing of the effects on the local and global ecosystem. Even if priced in a cost-reflective manner it is doubtful that consumer would understand (or even want to understand) the components that go into that price.

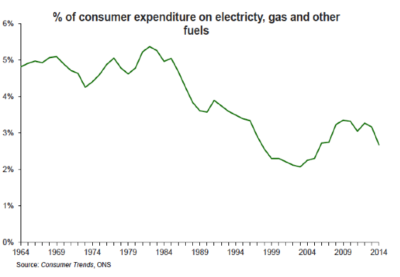

As such, engagement with the public around the topic of energy prices is challenging and  complex. Inevitably provision of services that are critical to the economy become highly politicised, both nationally and internationally. And while the media consistently report the rising costs of energy, according to a recent House of Commons Briefing Paper[1], the actual consumer expenditure on electricity, gas and other fuels has reduced from around 5% of income in the 1960s and 70s to around 3% in the last decade.

complex. Inevitably provision of services that are critical to the economy become highly politicised, both nationally and internationally. And while the media consistently report the rising costs of energy, according to a recent House of Commons Briefing Paper[1], the actual consumer expenditure on electricity, gas and other fuels has reduced from around 5% of income in the 1960s and 70s to around 3% in the last decade.

This is partly driven by the headline writers who often confuse price with cost and don’t appreciate the former can rise whilst the latter reduces with improved efficiency. However in the case of electricity it is also driven by the pattern of infrastructure investments. There were significant public investments in the 70s and 80s in nuclear and coal and associated network infrastructure, and a bonanza of natural gas in the 90s, but now we have spent our inheritance and the next wave of investment is overdue. Ultimately the end consumer will have to foot the bill.

Another confusion comes when commentators look to the wholesale price expecting to see some evidence of the market’s expectation of investment. For example Tom Hoines from Opus Energy highlighted at a conference earlier this year how wholesale prices actually decrease the further out you look. However the wholesale price is only an indicator of the short run marginal cost of generation (including subsidies), so with an increasing proportion of low-opex highly-subsidised renewables this is exactly what one would expect. Even for conventional fossil plant major investment is now paid for via the capacity mechanism, removing any need to recover capex and other long run costs via the spot price.

So the wholesale electricity price is becoming an irrelevance (as far as long term decisions are concerned) and investment is paid for via the various uplifts between wholesale price and retail price that are added in to cover the purchase of grid services, the Renewables Obligation payments, CFD subsidies and the capacity mechanism costs.

So it seems like we need a new paradigm for pricing energy services. Presently consumers pay a linear price based on energy alone and yet receive a whole host of services. Clearly a consumer with a demand weighted towards times of system stress is costing the system much more than one that takes the same energy at benign periods. Similarly one with a higher peak demand needs more infrastructure than one with the same energy spread more evenly. A prosumer that demands a frequency signal from the grid to allow their PV panel to generate should perhaps pay for the service received. A community energy group that is totally disconnected from the grid should be treated very differently to one that occasionally wants the national grid infrastructure there as back-up for its own generation.

The challenge is to understand and then define the basic services that are transferred via the electricity network. Energy is the simplest and reasonably well understood, but it is the one that is diminishing in both value and price. Others may be packaged differently depending on who is taking or giving the service: It may be a guaranteed level of availability or peak demand, a stable frequency signal or ability to absorb intermittent generation. The grid operator may express the system needs in terms of frequency response, reserve requirement or minimum inertia levels.

This is an area where ERP’s diverse membership of industry, government and academia can provide unique and independent insight in 2017. Untangling market prices and technology costs and relating them to the services the grid users want is the challenge, and identifying a new, fairer structure to pay for the grid the ultimate aim. Inevitably though, if energy service providers really want to move the conversation on from a simple price up or down analysis, they will have to focus their offerings on what delivers ultimate value to the consumer; whether that is mobility, lighting, comfortable temperatures or a lifetime of power bundled with an appliance. After all, all electrons are created equal, it is where, why and when they were moved that will become more relevant.

CLICK TO VOTE: I think this should be an ERP priority

>Next topic area

>Back to all topics list

[1] http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN04153